I have developed a model rehabilitation plan for achieving human bipedal walking based on the latest neurological background.

Many people feel uncertain about what to do and where to start when conducting rehabilitation for walking recovery.

Here, I have compiled interventions for improving walking, assuming individuals with hemiplegia due to stroke.

By reading this article, you will understand the neurological background of walking and be able to formulate a rehabilitation plan aimed at improving walking.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

Preparation for walking

Even when we talk about walking practice, it doesn't necessarily mean walking practice can be done right away.

There are several preparations needed before walking.

While I've written about several aspects here, it doesn't have to be in this exact order. All elements need to be in place.

Postural Control

During walking, the upper body (from the pelvis upward) must remain stable atop the locomotor system (the lower limbs, including the pelvis).

To achieve this, it is crucial not only for the trunk but also for the head (which houses vital sensory organs like the eyes and semicircular canals), neck, and upper limbs to be able to move independently.

The “passenger” is fundamentally responsible only for maintaining their own posture. Therefore, the normal walking mechanism performs best when the load on the “passenger” is minimized. The “passenger” must be an independent unit transported by the “locomotor.” This enables the “passenger” to perform various activities (multi-tasking) using the upper body, arms (or hands), and head, independent of forward movement.

Kirsten Gotz-Neumann, Understanding Gait: Gait Analysis in Physiotherapy, 2015

Postural control during walking requires trunk extension and a high center of mass (COM).

This is because a low COM indicates flexion somewhere in the body, which simultaneously implies poor alignment.

In other words, the passenger is not in an efficient state for postural maintenance, such as optimal muscle activity. This makes it difficult to achieve hip and trunk extension during the shock absorption phase of initial contact.

As walking speed increases to a certain degree, upper limb swing becomes visible, but this requires internal rotation of the body axis while the trunk remains vertically extended.

Sensori-Motor Relationship

When the foot (heel) makes contact, muscle activity occurs immediately, and the lower limbs provide support.

This is due to the skin sensation and muscle stretch that occur when the skin of the heel deforms.

While there is a phenomenon called the multi-joint kinetic chain, here we must consider not only the chain of movements but the entire process by which sensory information is converted into movement.

It is necessary to include peripheral sensory organs (skin, muscle spindles, tendon spindles), afferent fibers, the central nervous system (presumably the spinal cord and brainstem), efferent fibers, and skeletal muscle as effectors.

Since it cannot be seen with the naked eye, it is necessary to judge by observing movement, muscle contraction, and so on.

A combination of the movement (Synergy)

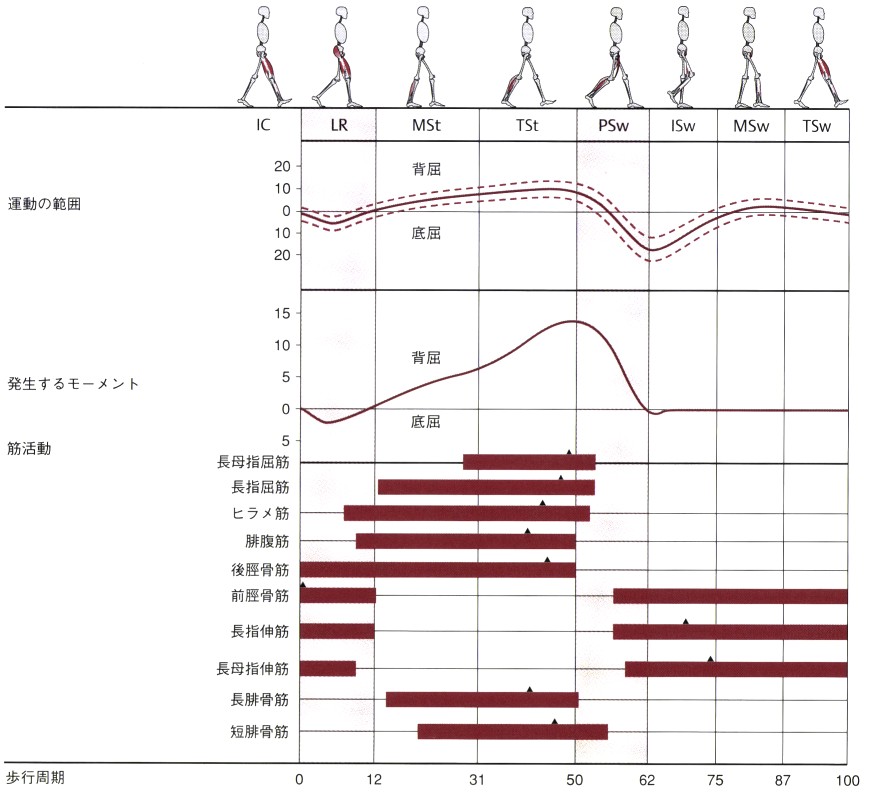

The act of walking is composed of several muscles working in coordination. Generally, a combination of four muscles (some papers cite three to five) enables the movement of walking.

This combination of muscles is called synergy, and it is thought to allow the brain to avoid having to command each muscle individually.

For example, when the rear foot pushes off the ground during walking, a synergy that simultaneously extends the hip and knee joints is used. This combination is also used during standing up and maintaining balance while standing. Identifying synergies that are not being used effectively and practicing using the muscles in different contexts is also important.

Practice in walking situations

Analysis aligned with the gait cycle is crucial for comprehensively capturing the entirety of walking.

Gait analysis requires examining the act of walking itself. The central nervous system represents the entire gait as a sequence of combined movements.

In other words, if the right leg feels heavy and difficult to swing forward, compensatory activity immediately occurs in the left lower limb and trunk.

It is important to analyze not only the paralyzed side but also the movement of the opposite side at that moment, as well as HAT (Head, Arm, Trunk).

When considering the common complaint from hemiplegic individuals—“I can't initiate movement on the paralyzed side”—this corresponds to PSw on one side and IC~LR on the other.

This “initiation” cannot occur without activity where the non-paralyzed hip flexes and extends, and the trunk extends upward.

Weight Transfer in the Double-stance Phase

Additionally, approximately 20% of the gait cycle is the double stance phase.

During this double stance phase, weight transfer occurs. This involves shifting weight from the paralyzed side to the non-paralyzed side, or vice versa.

It is also crucial not to overlook whether extension of the trunk and head/neck (avoiding lateral flexion) is maintained, not just in both lower limbs.

Speed and Rhythm Experience

In the Double Stance phase, trunk rotation and upper limb swing also occur. However, in the gait of healthy adults, arm swing is not observed until walking speeds reach a certain threshold (approximately 2.4 km/h).

To achieve the gait pattern of healthy adults, it is necessary to gain experience walking at a faster and more rhythmic pace.

Summary

I've outlined the essential elements required to acquire walking. I believe progress toward achieving walking occurs when each of these components comes together.

Please revisit the walking analysis once more.